Two interesting columns on Gamasutra caught my attention recently. Both of them have been written by people I follow for a long time and they both debunk myths about video games. On the one hand, Ian Bogost writes about how hard it is to make games and the inherent problem of "serious games" or "gamification" approaches. His point is that making game is super hard and that making good games to serve external purposes is even harder. Some excerpts I found important:

"key game mechanics are the operational parts of games that produce an experience of interest, enlightenment, terror, fascination, hope, or any number of other sensations. Points and levels and the like are mere gestures that provide structure and measure progress within such a system. (...) The sanctity of games' unique means of expression is just not of much concern to the gamifiers. Instead they value facility -- the easiest way possible to capture some of the fairy dust of games and spread it upon products and services. Games or points isn't the point -- for gamifiers, there's no difference. It's the -ification that's most important (...) In the modern marketing business, the best solutions are generic ones, ideas that can be repeated without much thought from brand to brand, billed by consultants and agencies at a clear markup. Gamification offers this exactly. No thinking is required, just simple, absentminded iteration and the promise of empty metrics to prove its value."

On the other hand, Greg Costikyan gives his perspective on the "social" of social games. He basically wonder about the asocial or even antisocial characters of these games:

" Developers of social games have clearly given great thought to using the social graph to foster player acquisition, retention, and monetization; but as far as I can see, no thought whatsoever has given to the use of player connections to foster interesting gameplay. It's all about the money, and not at all about the socialization.

The peculiarity of this is that social networks are actually far better suited than most online environments to fostering social gameplay. Messaging and chat are built into the system, and need not be separately implemented by developers; but more importantly, the social graph allows players to interact with people who are their actual friends."

Interestingly, Costikyan then describes what could be a "social gameplay": the value of having teams, diplomacy, negotiated trade, resource competition, hierarchy or performative play (not as "winning point to get the best performance", rather "speaking and acting in character").

Why do I blog this? These two columns are important and interesting read as they reduce the inflated reputation of two current "trend" candidates. They also offer relevant counter-versions about what is relevant in game design.

Design failures and recurring non-products is of course a favorite topic of mine. Hence, a paper entitled "

Design failures and recurring non-products is of course a favorite topic of mine. Hence, a paper entitled " A chalk map found on a wall in Paris last Monday. An interesting example of a temporary object employed for specific purposes.

A chalk map found on a wall in Paris last Monday. An interesting example of a temporary object employed for specific purposes.

Anyone interested in robots and networked objects in multi-functions artifacts may be intrigued by this gorgeous AM/FM restroom radio with telephone that I ran across at the flea market the other day.

Anyone interested in robots and networked objects in multi-functions artifacts may be intrigued by this gorgeous AM/FM restroom radio with telephone that I ran across at the flea market the other day.

The ubiquitous presence of cell phone towers in urban and rural landscapes have led to protestation against their visual presence (the ugly mast/transmitter aesthetics) and their electromagnetic waves (which are invisible). A side-effect of people's "need" for uninterrupted connectivity, the design and building of phone towers is now influenced by various strategies. One of them consist in the use of camouflage techniques... and obviously the "natural" metaphor plays an important role here, as attested by these examples encountered in Lipari, Sicily last week.

The ubiquitous presence of cell phone towers in urban and rural landscapes have led to protestation against their visual presence (the ugly mast/transmitter aesthetics) and their electromagnetic waves (which are invisible). A side-effect of people's "need" for uninterrupted connectivity, the design and building of phone towers is now influenced by various strategies. One of them consist in the use of camouflage techniques... and obviously the "natural" metaphor plays an important role here, as attested by these examples encountered in Lipari, Sicily last week.

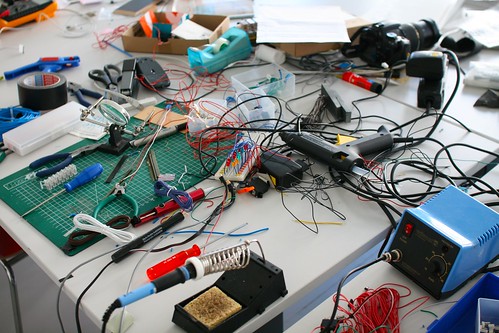

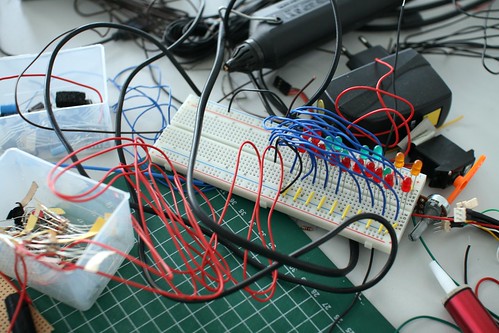

(Networked objects being designed at the

(Networked objects being designed at the  (Potential candidates as blank objects meant to receive memories?)

(Potential candidates as blank objects meant to receive memories?)

"Take me, sit on me, love me" :)

"Take me, sit on me, love me" :)