[Last year, I wrote a paper for a workshop at a human-computer interaction conference about the user experience of video games, actually it briefly presents the work I am doing with game companies. The paper was not accepted and I thought it would be pertinent to leave it online anyway]

Introduction

Video game companies have now integrated the need to deploy user-centered design and evaluation methods to enhance players experiences. This has led them to hire cognitive psychology researchers, human-computer interface specialists, develop in-house usability labs or subcontract tests and research to companies or academic labs. Although, very often, methods has been directly translated form classic HCI and usability, this game experience analysis started to gain weights through publications. This situation acknowledges the importance of setting a proper method for user-centered game design, as opposed to the one applied for “productivity applications” or web services. The Microsoft Game User Research Group for example has been very productive on that line of research (see for example [5]) with detailed methods such as usability tests, Rapid Iterative Test and Evaluation [4] or consumer playtests [1]. Usability test is definitely the most common method currently given its relevance to identify interfaces flaws as well as factors that lower the fun to play through behavioral analysis.

That said, most of the methods deployed by the industry seem to rely heavily on quantitative and experimental paradigms inherited from the cognitive sciences tradition in human-computer interaction (see [2]). Studies are often conducted in corporate laboratory settings in which myriads of players come visit and spend hours playing new products. Survey, ratings, logfile analysis, brief interviews (and sometimes experimental studies) are employed to apprehend users’ experiences and implications for game or level designers are fed back into game development processes.

While these approaches proves to be fruitful (as reported by the aforementioned papers which describe some case studies), this situation only accounts for a limited portion of what HCI and user-centered design could bring to table in terms of game user research. Too often, the “almost-clinical” laboratory usability test is deployed without any further thoughts regarding how players might experience the product “in the wild”. For example, this kind of studies does not take into account how the activity of gaming is organized, and how the physical and social context can be important to support playful activities.

What we propose is to step back for a while and consider a complementary approach to gain a more holistic view of how a game product is experienced. To do so, we will describe two examples from our research carried out in partnership with a game studio.

Examples from field studies

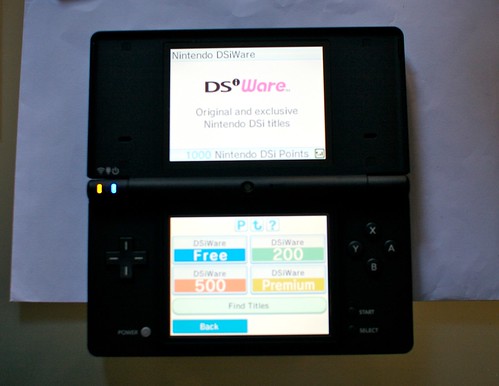

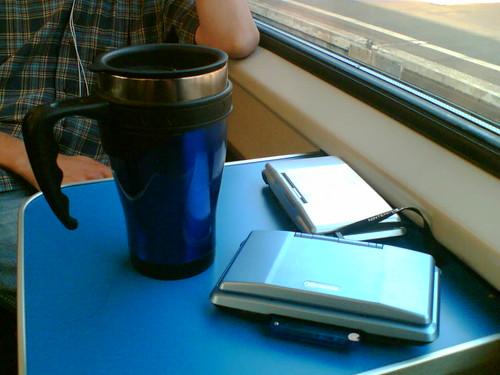

Our first example depicted on Figure 1 shows the console of an informant: a Nintendo DS with a post-it that says “Flea market on Saturday” and an exclamation mark. The player of “Animal Crossing” indeed left this as a reminder that two days ahead, there would be a flea market in the digital environment. This is important in the context of that game because it will allow him to sell digital items to non-playable characters in the game.

This post-it is only an example among numerous uses of external resources to complement or help the gameplay. Player-created maps of digital environments xeroxed and exchanged in schools in the nineties is another example of such behavior. Magazines, books and digital environment maps are also prominent examples of that phenomenon, which eventually leads to business opportunities. Some video game editors indeed start publishing material (books, maps, cards) and try to connect it to the game design (by allowing secret game challenges through elements disseminated in comics for example).

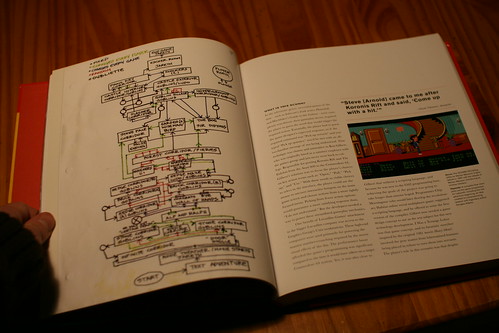

Figure 2 shows another example that highlights the social character of play. This group of Japanese kids is participating the game experience, although there is only one child holding a portable console. The picture represented here is only one example of collective play along many that we encountered, both in mobile of fixed settings. They indicate that playing a video-game is much more than holding an input controller since participants (rather than “The Player”) have different roles ranging from giving advices, scanning the digital environment to find cues, discussing previous encounters with NPCs or controlling the game character.

Another intriguing results from a study about Animal Crossing on the Nintendo DS has revealed that some players share the game and the portable console with others. An adult described how he played with his kid asynchronously: he hides messages and objects in certain places and his son locates them, displace them and eventually hide others. The result of this is the creation of a circular form of game-play that emerged from the players’ shared practice of a single console.

Conclusion

Although this looks very basic and obvious, these three examples correspond to two ways to frame cognition and problem solving: “Distributed Cognition” [3] and “Situated Action” [6]. While the former stresses that cognition is distributed the objects, individuals, and tools in our environment, Situated Action emphasizes the interrelationship between problem solving and its context of performance, mostly social. The important lesson here is that problem solving, such as interacting with a video-game is not confined to the individual but is both influenced and permitted by external factors such as other partners (playing or not as we have seen) or artifacts such as paper, pens, post-its, guidebooks, etc. Whereas usability testing relates to more individual model of cognition, Situated Action or Distributed Cognition imply that exploring and describing the context of play is of crux importance to fully grasp the user experience of games. Employing ethnographic methodologies, as proposed by these two Cognitive Sciences frameworks, can fulfill such goal by focusing on a qualitative examination of human behavior. It is however important to highlight the fact that investigating how, where and with whom people play is not meant to replace more conventional test. Rather, one can see this as a complement to understand phenomenon such as the discontinuity of gaming or the use of external resources while playing.

One of the reasons why this approach can be valuable is that results drawn from ethnographic research of gaming can be relevant to find unarticulated opportunities. For example, by explicitly requiring the use of external resource or the possibility to have challenges designed for multiple players as shown in the Animal Crossing example we described.

In the end, what this article stressed is that playing video-games is a broad experience which can be influenced by lots of factors that could be documented. And this material is worthwhile to design a more holistic vision of a product.

References

[1] Davis, J., Steury, K., & Pagulayan, R. A survey method for assessing perceptions of a game: The consumer playtest in game design. Game Studies: the International Journal of Computer Game Research, 5(1) (2005).

[2] Fulton, B. (2002). Beyond Psychological Theory: Getting Data that Improve Games. Game Developer's Conference 2002 Proceedings, San Jose CA, March 2002. Available at: http://www.gamasutra.com/gdc2002/features/fulton/fulton_01.htm

[3] Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the Wild, MIT Press.

[4] Medlock, M. C., Wixon, D., Terrano, M., Romero, R., Fulton, B. (2002). Using the RITE Method to improve products: a definition and a case study. Usability Professionals Association, Orlando FL July (2002). Available at: http://download.microsoft.com/download/5/c/c/5cc406a0-0f87-4b94-bf80-dbc707db4fe1/mgsut_MWTRF02.doc.doc

[5] Pagulayan, R. J., Keeker, K., Wixon, D., Romero, R., & Fuller, T. User-centered design in games. In J. Jacko and A. Sears (Eds.), Handbook for Human-Computer Interaction in Interactive Systems, pp.883-906. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (2002).

[6] Suchman, L.A. (1987). Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-Machine Communication. Cambridge: Cambridge Press.

[Now it's also interesting to add a short note about WHY the paper has not been accepted The first reviewer was unhappy by the fact that many ethnographies of game-playing have been published. Although this is entirely true in academia, it's definitely not the case in the industry (where ethnography is seldom employed in playtests). And my mistake may have been that I frame the paper in an game industry perspective, using the literature about gaming usability. The second reviewer wanted a more extensive description of a field study and less a scratch-the-surface approach that I adopted. My problem of course is that it's always difficult to describe results more deeply because most of the data are confidential... This is why I stayed at a general level]